spagg

spagg.RmdIntroduction

In this vignette, we illustrate how to use the spagg

package to analyze multiple spatial point patterns. In particular, we

will show how to use the functions in this package to construct an

aggregate spatial summary statistic across point patterns grouped

together by some higher level factor, such as by tissue sample. We will

then use this aggregated spatial summary statistic as a predictor in a

linear model for a group-level/sample-level outcome.

The motivation behind spagg is that analyses of data

from multiplexed immunofluorescence and spatial proteomics platforms may

involve multiple regions-of-interest (ROIs) imaged from the same tissue

sample. Each ROI shows the spatial location of cells in tissue which can

be treated as a spatial point pattern. Access to multiple ROIs per

tissue sample can complicate associative analyses seeking to

characterize associations between the spatial distribution of cells in

tissue and sample-level outcomes because we need to test for an

association between a single sample-level outcome (e.g. survival or

case/control status) and multiple spatial summary statistics.

This vignette will use simulated spatial point pattern data. To see

how this data was generated, please see

spagg > data-raw > simdata.R.

Loading in the Data and Plotting

We start by loading in the spagg package and our

simulated data. We show the first few lines of the dataset below. The

dataset is organized so as to mimic the structure of single-cell,

spatial images produced by multiplexed immunofluorescence and spatial

proteomics platforms. Each row corresponds to a detected cell, which is

enumerated by the cell.id column. The cells are grouped

together by samples, denoted by the PID column and by

images within those samples, denoted by the id column. The

x and y columns give the (x,y) coordinates of

each cell. The type column denotes the cell type for the

corresponding row. In this simulated dataset, the possible cell types

are a and b. Finally, the out

column gives the sample-level endpoint with which we are interested in

performing associative analyses. In this simulated dataset, the

out column is a binary 1 or 0

indicator.

# Load in packages

library(spagg)

library(ggplot2)

library(cowplot)

library(spatstat)

#> Loading required package: spatstat.data

#> Loading required package: spatstat.univar

#> spatstat.univar 3.0-0

#> Loading required package: spatstat.geom

#> spatstat.geom 3.3-2

#> Loading required package: spatstat.random

#> spatstat.random 3.3-1

#> Loading required package: spatstat.explore

#> Loading required package: nlme

#> spatstat.explore 3.3-1

#> Loading required package: spatstat.model

#> Loading required package: rpart

#> spatstat.model 3.3-1

#> Loading required package: spatstat.linnet

#> spatstat.linnet 3.2-1

#>

#> spatstat 3.1-1

#> For an introduction to spatstat, type 'beginner'

library(dplyr)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'dplyr'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:nlme':

#>

#> collapse

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> filter, lag

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

# Load in data and show first few lines

data(simdata)

head(simdata)

#> PID id x y cell.id type out

#> 1 1 PID.1.image.1 27.09050 63.03496 1 a 1

#> 2 1 PID.1.image.1 21.97141 63.93355 2 a 1

#> 3 1 PID.1.image.1 18.70571 63.51489 3 b 1

#> 4 1 PID.1.image.1 20.29608 68.71936 4 b 1

#> 5 1 PID.1.image.1 22.74318 69.08458 5 b 1

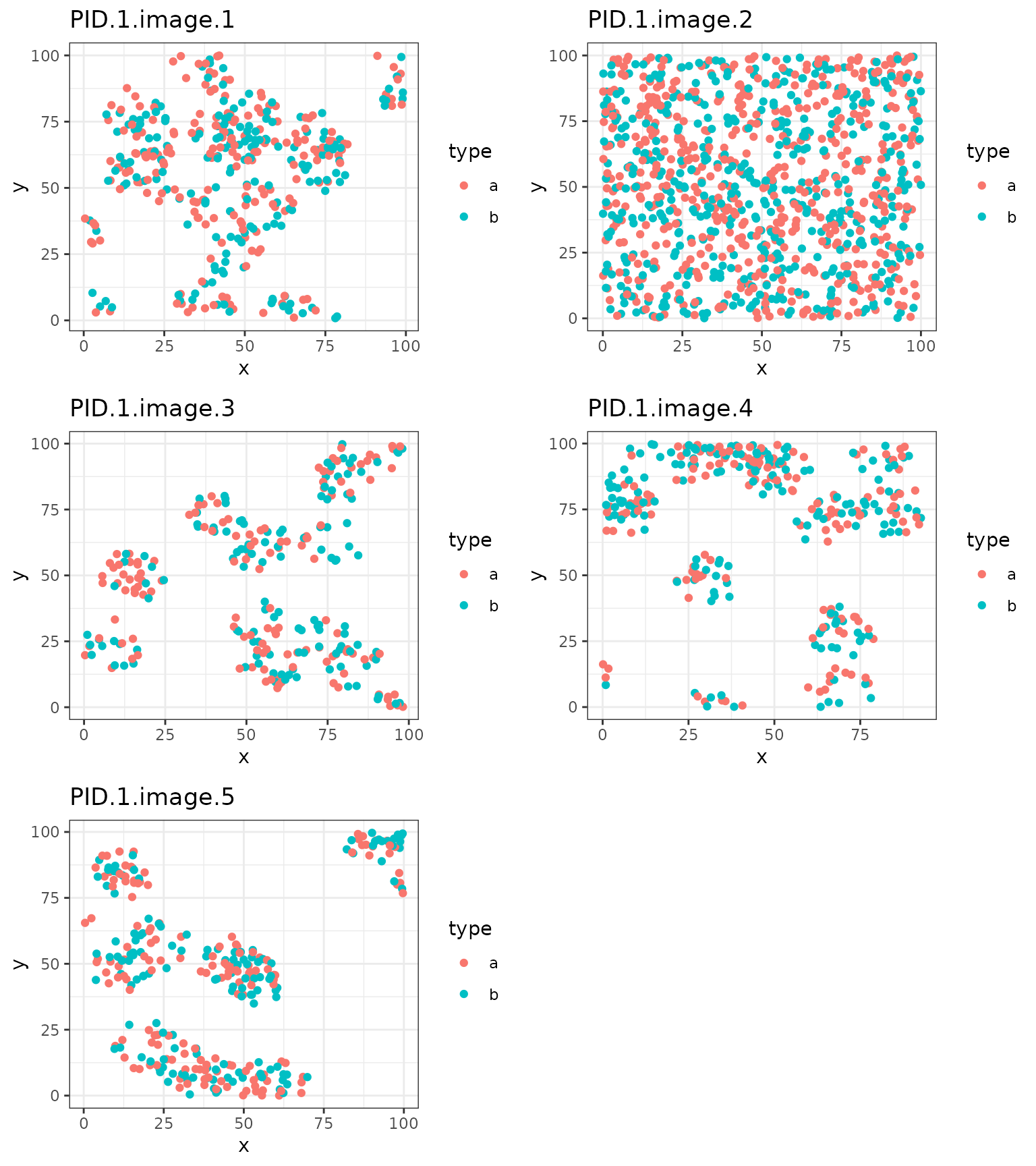

#> 6 1 PID.1.image.1 17.47202 75.63201 6 b 1We can plot the images for PID=1. This can be a helpful

tool to visually assess variation in the spatial distribution of cells

across ROIs.

# Plot the images for PID=1 --

# Save the image IDs

PID.1.image.ids <- unique(simdata$id[simdata$PID == 1])

# Create a list of plots

plot.list <- lapply(1:length(PID.1.image.ids), function(i) list())

# Iterate through the image IDs and create a plot for each

for (id.i in PID.1.image.ids) {

pp <- simdata %>%

dplyr::filter(id == id.i) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, color = type)) +

geom_point() +

theme_bw() +

ggtitle(id.i)

plot.list[[which(PID.1.image.ids == id.i)]] <- pp

}

# Construct the full plot

cowplot::plot_grid(plot.list[[1]], plot.list[[2]],

plot.list[[3]], plot.list[[4]],

plot.list[[5]], nrow = 3, ncol = 2) The above plots show simulated data, but illustrate a common challenge

that arises in analyzing grouped point patterns reflecting multiple ROIs

of a tissue sample: heterogeneity in the spatial clustering patterns.

Each ROI shows a different clusterig pattern among the

The above plots show simulated data, but illustrate a common challenge

that arises in analyzing grouped point patterns reflecting multiple ROIs

of a tissue sample: heterogeneity in the spatial clustering patterns.

Each ROI shows a different clusterig pattern among the a

and b cell types.

We are going to use the spatial summary statistic, Ripley’s K, to

characterize the degree of adherence to clustering, repulsion, or

complete spatial randomness in each ROI. The spagg package

the contains five approaches for handling multiple spatial summary

statistics for associative analyses. Three of these approaches are

weighted aggregations of the spatial summaries using fixed weights. The

other two are ensemble approaches which generate random weights used to

construct weighted aggregations. Within each ensemble replication, we

test for an association between the weighted aggregation and the

sample-level outcome. We then ensemble the resulting p-values for an

omnibus test.

We first start by illustrating the weighted aggregations.

Weighted Aggregations

We will first consider different approaches to averaging Ripely’s K across ROIs within a sample. Let’s start by defining some notation. Suppose for sample we have ROIs. Let be the number of cells in sample ROI . Let represent the area of sample ROI . Let represent the spatial distribution of cells evaluate at radius .

spagg contains implementations for the following three

weighted averages:

(Diggle, Lange, and Beneš (1991)), (Baddeley et al. (1993)), and (Landau, Rabe-Hesketh, and Everall (2004)) were each proposed as approaches to aggregating replicated Ripley’s K statistics. The motivation behind each of these aggregations is to weight each Ripley’s K statistic by its sampling variance. However, the sampling variance is generally difficult to write down explicitly for Ripley’s K so each method relies on an approximation. The accuracy of the approximation relies on whether the intensity of the spatial point pattern (the ratio of the number of cells divided by the image area) is consistent or varied across ROIs. If the intensity is consistent, all methods should yield similar average Ripley’s K statistics and, in turn, perform similarly-well for hypothesis testing. If the intensity is different across ROIs, and also informative in predicting the outcome, the Landau mean may perform better.

We first consider a univariate analysis where we analyze only one

cell type. We start with cell type a only and its

associations with sample-level outcomes. We estimate Ripley’s K for

on each ROI. Note this may take several seconds (up to 30 seconds) to

run.

# Set the radius

r <- 30

# Save the image IDs

ids <- unique(simdata$id)

# Initialize a data.frame to store the results for each ROI

cell.a.results <- simdata %>%

dplyr::select(PID, id) %>%

dplyr::distinct() %>%

dplyr::mutate(spatial = NA,

npoints = NA,

area = NA)

# Iterate through the ROIs (this will take a few seconds)

for (i in 1:length(ids)) {

# Save the ith image

image.i <- simdata %>%

dplyr::filter(id == ids[i]) %>%

dplyr::select(x, y, type)

# Convert to a point process object

w <- spatstat.geom::convexhull.xy(image.i$x, image.i$y)

image.i.subset <- image.i %>% dplyr::filter(type == "a")

image.ppp <- spatstat.geom::as.ppp(image.i.subset, W = w)

spatstat.geom::marks(image.ppp) <- image.i.subset$type

# Compute Kest

Ki <- spatstat.explore::Kest(image.ppp, r = 0:r)

# Calculate the number of points

npoints.i <- spatstat.geom::npoints(image.ppp)

# Calculate the area

area.i <- spatstat.geom::area(image.ppp)

# Save the results

cell.a.results[cell.a.results$id == ids[i],]$spatial <- Ki$iso[r+1]

cell.a.results[cell.a.results$id == ids[i],]$npoints <- npoints.i

cell.a.results[cell.a.results$id == ids[i],]$area <- area.i

}

# View the first few rows

head(cell.a.results)

#> PID id spatial npoints area

#> 1 1 PID.1.image.1 3402.412 206 8298.469

#> 2 1 PID.1.image.2 2779.338 538 9844.653

#> 3 1 PID.1.image.3 2623.948 134 7157.505

#> 4 1 PID.1.image.4 3382.632 151 8314.183

#> 5 1 PID.1.image.5 2911.225 157 7682.093

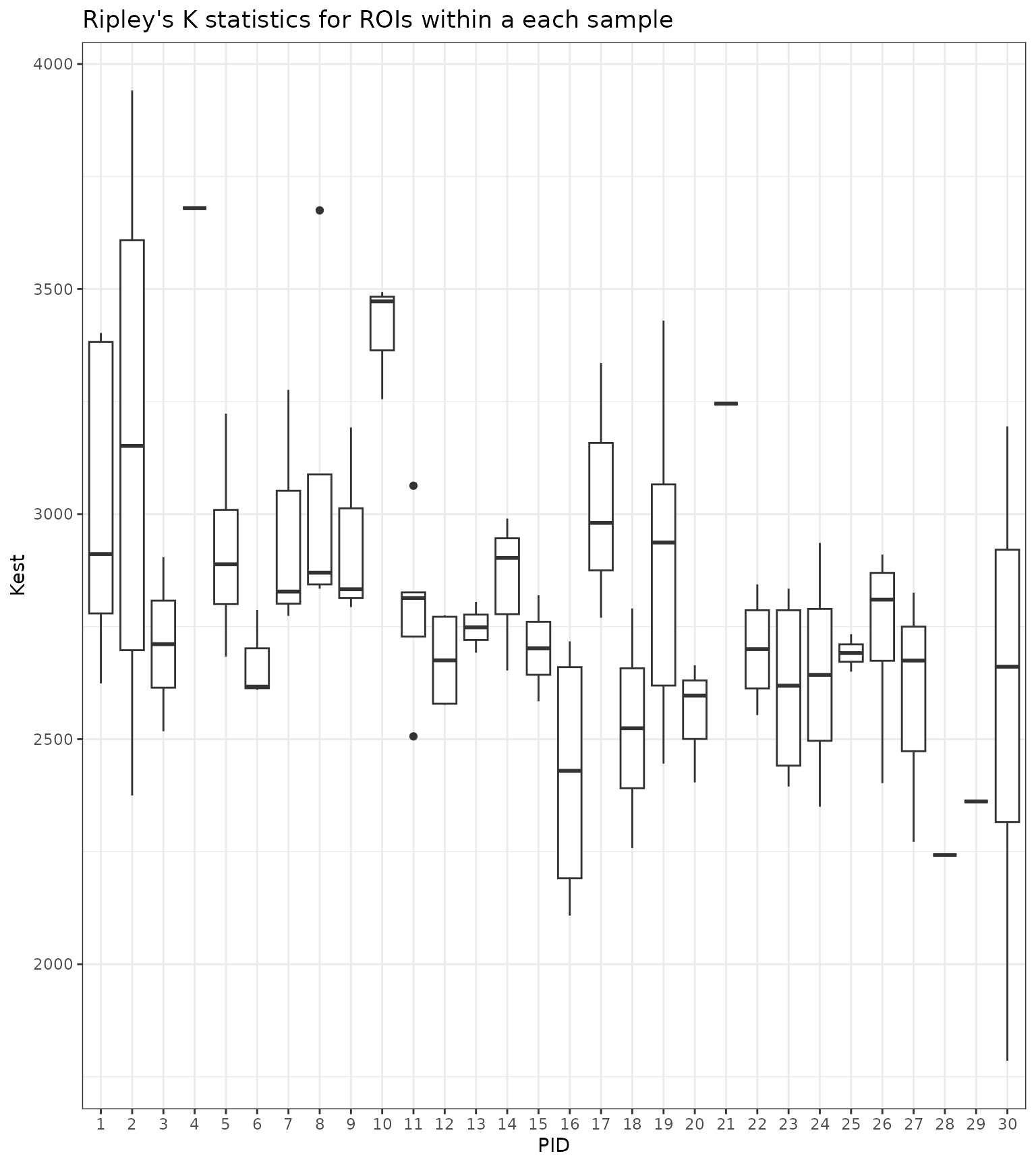

#> 6 2 PID.2.image.1 2374.916 62 7080.358We can now visualize the distribution of the spatial summaries within

each image as an illustration of the variation in spatial distribution

of cells of type a across ROIs.

# Visualize the distribution of spatial summaries within each sample

cell.a.results %>%

dplyr::mutate(PID = factor(PID)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PID, y = spatial, group = PID)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Ripley's K statistics for ROIs within a each sample") +

ylab("Kest")

As the above plot illustrates, there can be considerable variation in the spatial summary statistic values within a single sample.

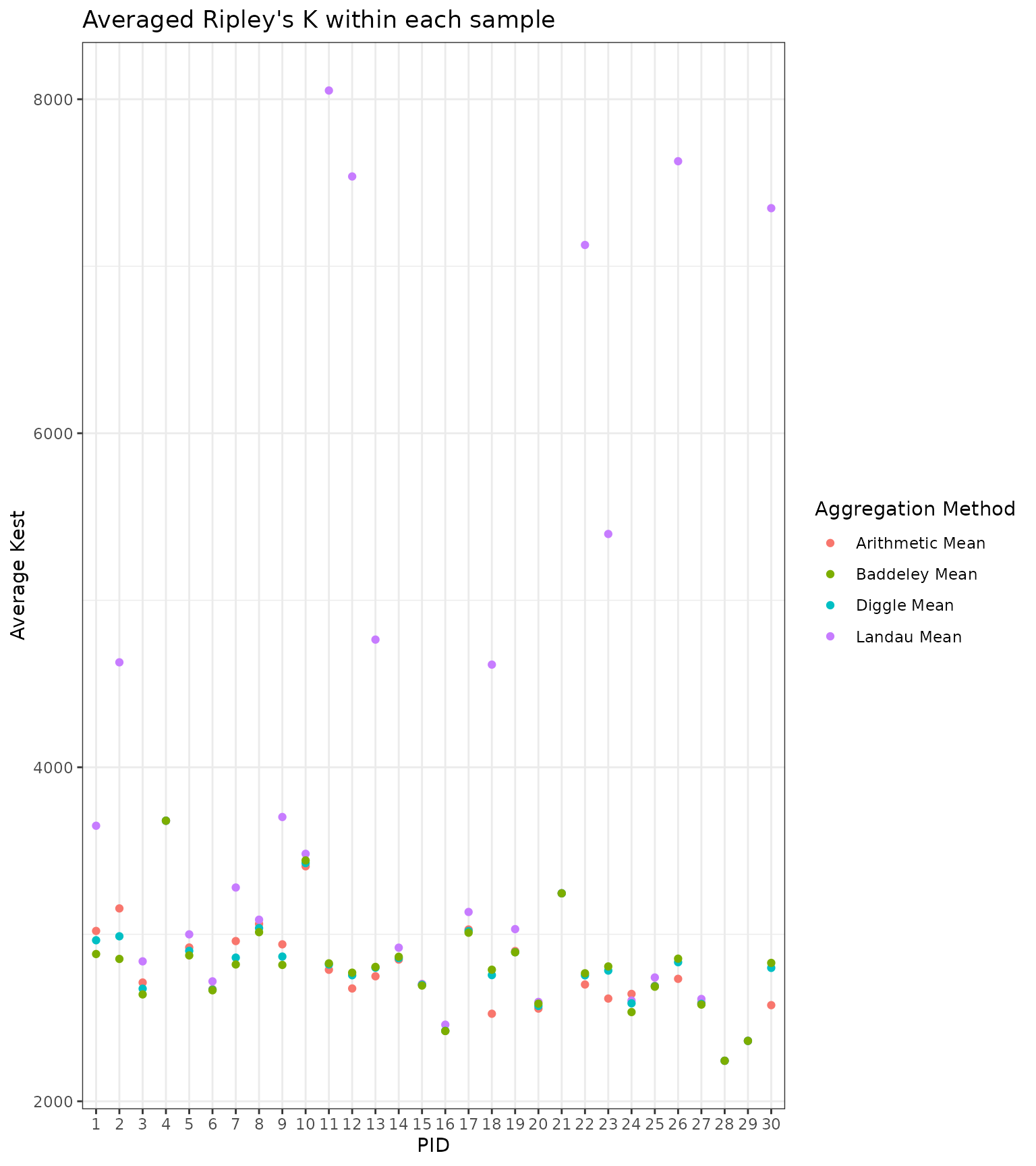

After that, we will compute the weighted averages given above. We will also compute a standard arithmetic mean as a comparison. Below, we visualize the spread of the various spatial aggregation methods within each sample. For some samples, the averages yield similar values. For others, the averages exhibit large variation, suggesting they up- or down-weight certain ROIs depending on the area of the ROI or the number of cells.

# Compute averages

cell.a.results_mean <- cell.a.results %>%

dplyr::group_by(PID) %>%

dplyr::summarise_at(dplyr::vars(spatial),

list(~mean(.x),

~landau.avg(K.vec = .x, area.vec = area, n.vec = npoints),

~diggle.avg(K.vec = .x, n.vec = npoints),

~baddeley.avg(K.vec = .x, n.vec = npoints)))

# Plot the averages

cell.a.results_mean %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(2:5, names_to = "mean", values_to = "value") %>%

dplyr::mutate(mean = recode(mean,

"mean" = "Arithmetic Mean",

"landau.avg" = "Landau Mean",

"diggle.avg" = "Diggle Mean",

"baddeley.avg" = "Baddeley Mean")) %>%

dplyr::mutate(PID = factor(PID)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PID, y = value, group = mean, color = mean)) +

geom_point() +

theme_bw() +

ylab("Average Kest") +

ggtitle("Averaged Ripley's K within each sample") +

scale_color_discrete(name = "Aggregation Method")

We now have a data.frame with a column corresponding to each average.

We can add in the outcome variable, out, so we can do

association testing with the aggregated Ripley’s K statistics. We would

like to compare if the aggregated Ripley’s K statistics are equal

between cases (out=1) and controls (out=0). In

other words, we would like to test if the average spatial

distribution of cells across ROIs is the same between these two

groups.

# First, check the ordering matches

all(unique(simdata$PID) == cell.a.results_mean$PID) # TRUE!

#> [1] TRUE

# Add in the outcome

cell.a.results_mean$out <- simdata %>%

dplyr::select(PID, out) %>%

dplyr::distinct() %>%

dplyr::select(out) %>%

unlist()

# Test for an association between CD4 T cell spatial distributions and MHCII-high status

mean.glm <- glm(out ~ mean, data = cell.a.results_mean, family = binomial())

diggle.glm <- glm(out ~ diggle.avg, data = cell.a.results_mean, family = binomial())

baddeley.glm <- glm(out ~ baddeley.avg, data = cell.a.results_mean, family = binomial())

landau.glm <- glm(out ~ landau.avg, data = cell.a.results_mean, family = binomial())

# Save the p-values in a table and display

cell.a.pvals <- data.frame(

Method = c("Mean", "Diggle", "Baddeley", "Landau"),

P.Value = c(summary(mean.glm)$coef[2,4], summary(diggle.glm)$coef[2,4],

summary(baddeley.glm)$coef[2,4], summary(landau.glm)$coef[2,4])

)

# Show the results

cell.a.pvals

#> Method P.Value

#> 1 Mean 0.006060067

#> 2 Diggle 0.023752779

#> 3 Baddeley 0.040878265

#> 4 Landau 0.205325277Using a standard mean, the Diggle method, and the Baddeley approach,

we found a significant association between the spatial distribution of

cell type a and outcomes. We did not find this association,

however, using the Landau mean.

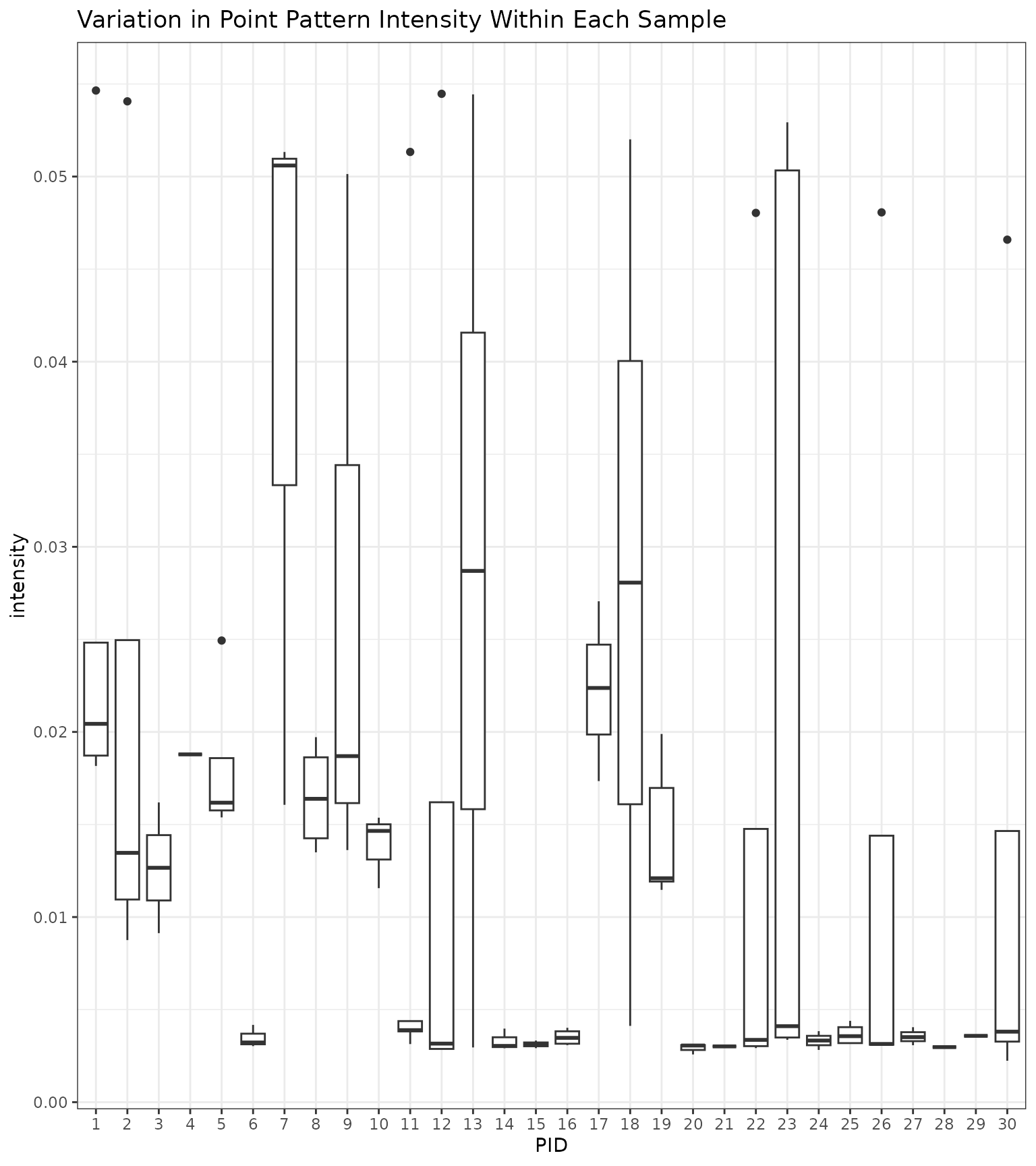

To explore the varied performance of these methods a bit more, we can

plot the intensity of cell type a within each ROI and

examine the variation across samples, as shown below. There is

considerable variation across samples and considerable variation within

some samples. Samples 4 and 6, for example, show very little variation

across ROIs. However, Sample 4 only had 1 image. Other samples, showed

more variation, like Samples 1 and 2. The overall spread in variation,

however, was only between 0.002 and 0.05.

# Calculate intensity for each ROI and plot

cell.a.results %>%

dplyr::mutate(intensity = npoints/area) %>%

dplyr::mutate(PID = factor(PID)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = PID, y = intensity, group = PID)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Variation in Point Pattern Intensity Within Each Sample")

# How many ROIs did each sample have?

simdata %>% dplyr::select(PID, id) %>% dplyr::group_by(PID) %>% dplyr::summarise(n = n()) %>% head(10)

#> # A tibble: 10 × 2

#> PID n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 1 2272

#> 2 2 1570

#> 3 3 466

#> 4 4 318

#> 5 5 1098

#> 6 6 170

#> 7 7 2292

#> 8 8 1004

#> 9 9 1419

#> 10 10 702

# Calculate the range in intensity

cell.a.results %>%

dplyr::mutate(intensity = npoints/area) %>%

dplyr::summarise(min.intensity = min(intensity),

max.intensity = max(intensity))

#> min.intensity max.intensity

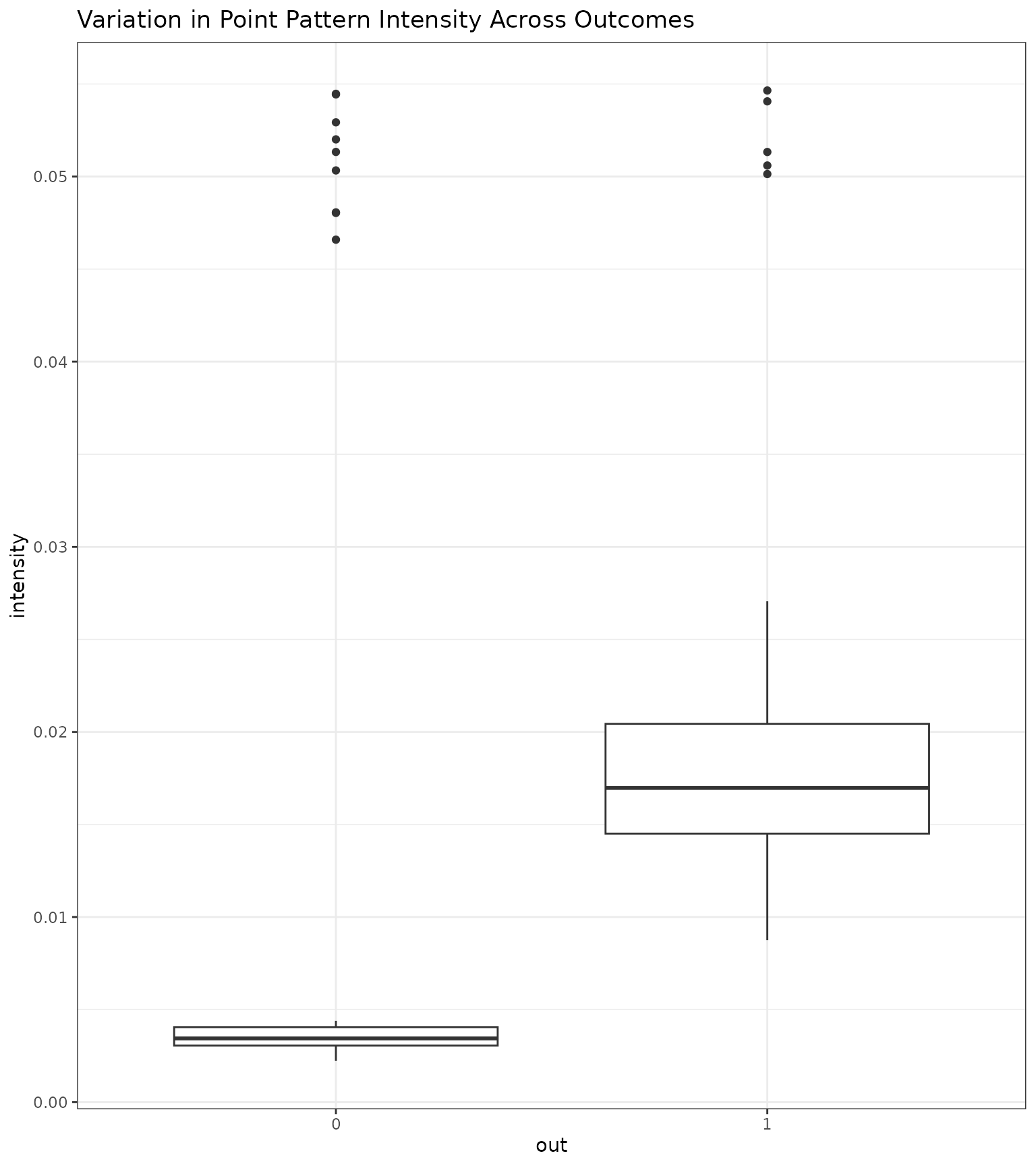

#> 1 0.002237422 0.05464895We can also examine if the intensity differed between outcomes. Below

we plot the intensities across ROIs and examine if this associates with

case (out=1) or control (out=0) status. Below,

we see that there was some variation in ROI intensity across outcomes.

Nonetheless, the Landau mean still did not perform best.

# Add in the outcome

cell.a.results$out <- simdata %>%

dplyr::select(PID, id, out) %>%

dplyr::distinct() %>%

dplyr::select(out) %>%

unlist()

# Plot

cell.a.results %>%

dplyr::mutate(intensity = npoints/area) %>%

dplyr::mutate(out = factor(out)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = out, y = intensity)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Variation in Point Pattern Intensity Across Outcomes")

We also consider a bivariate analysis where we examine the bivariate

colocalization of cell types a and b. We

follow a similar series of steps, but instead use the

Kcross function to characterize the colocalization of these

cell types.

# Set the radius

r <- 30

# Initialize a data.frame to store the results for each ROI

cell.ab.results <- simdata %>%

dplyr::select(PID, id) %>%

dplyr::distinct() %>%

dplyr::mutate(spatial = NA,

npoints = NA,

area = NA)

# Iterate through the ROIs (this will take a few seconds)

for (i in 1:length(ids)) {

# Save the ith image

image.i <- simdata %>%

dplyr::filter(id == ids[i]) %>%

dplyr::select(x, y, type)

# Convert to a point process object

w <- spatstat.geom::convexhull.xy(image.i$x, image.i$y)

image.ppp <- spatstat.geom::as.ppp(image.i, W = w)

spatstat.geom::marks(image.ppp) <- factor(image.i$type)

# Compute Kest

Ki <- spatstat.explore::Kcross(image.ppp, i = "a", j = "b", r = 0:r)

# Calculate the number of points

npoints.i <- spatstat.geom::npoints(image.ppp)

# Calculate the area

area.i <- spatstat.geom::area(image.ppp)

# Save the results

cell.ab.results[cell.ab.results$id == ids[i],]$spatial <- Ki$iso[r+1]

cell.ab.results[cell.ab.results$id == ids[i],]$npoints <- npoints.i

cell.ab.results[cell.ab.results$id == ids[i],]$area <- area.i

}

# View the first few rows

head(cell.ab.results)

#> PID id spatial npoints area

#> 1 1 PID.1.image.1 3352.665 388 8298.469

#> 2 1 PID.1.image.2 2778.717 1010 9844.653

#> 3 1 PID.1.image.3 2695.169 257 7157.505

#> 4 1 PID.1.image.4 3406.225 316 8314.183

#> 5 1 PID.1.image.5 2947.781 301 7682.093

#> 6 2 PID.2.image.1 2449.192 124 7080.358Following the same steps as above, we will compute the averages

within each PID and test for an association with the

outcome.

# Compute averages

cell.ab.results_mean <- cell.ab.results %>%

dplyr::group_by(PID) %>%

dplyr::summarise_at(dplyr::vars(spatial),

list(~mean(.x),

~landau.avg(K.vec = .x, area.vec = area, n.vec = npoints),

~diggle.avg(K.vec = .x, n.vec = npoints),

~baddeley.avg(K.vec = .x, n.vec = npoints)))

# First, check the ordering matches

all(unique(simdata$PID) == cell.ab.results_mean$PID) # TRUE!

#> [1] TRUE

# Add in the outcome

cell.ab.results_mean$out <- simdata %>%

dplyr::select(PID, out) %>%

dplyr::distinct() %>%

dplyr::select(out) %>%

unlist()

# Test for an association between CD4 T cell spatial distributions and MHCII-high status

mean.ab.glm <- glm(out ~ mean, data = cell.ab.results_mean, family = binomial())

diggle.ab.glm <- glm(out ~ diggle.avg, data = cell.ab.results_mean, family = binomial())

baddeley.ab.glm <- glm(out ~ baddeley.avg, data = cell.ab.results_mean, family = binomial())

landau.ab.glm <- glm(out ~ landau.avg, data = cell.ab.results_mean, family = binomial())

# Save the p-values in a table and display

cell.ab.pvals <- data.frame(

Method = c("Mean", "Diggle", "Baddeley", "Landau"),

P.Value = c(summary(mean.ab.glm)$coef[2,4], summary(diggle.ab.glm)$coef[2,4],

summary(baddeley.ab.glm)$coef[2,4], summary(baddeley.ab.glm)$coef[2,4])

)

# Show the results

cell.ab.pvals

#> Method P.Value

#> 1 Mean 0.02393126

#> 2 Diggle 0.01362797

#> 3 Baddeley 0.05261129

#> 4 Landau 0.05261129Here we found a significant association between the spatial

colocalization of cell types a and b with

outcomes using a standard arithmetic mean and using the Diggle mean but

not using the Baddeley or Landau mean.

Ensemble Approaches

We now illustrate using ensemble testing to test the same hypothesis,

whether the spatial distribution of cells is equal between cases

(out=1) and controls (out=0). These ensemble

approaches consider multiple random weights used to construct the

aggregations of the spatial summary statistics. For each set of random

weights, we test for an association between the weighted aggregation and

outcome. We repeat this for many random weights and combine the

resulting p-values using a p-value combination method. For this purpose,

we use the Cauchy combination test (Liu and Xie

(2020)).

The motivation behind these ensemble approaches is that the best set of weights (the weights that will yield the highest power) is generally unknown at the outset. For this reason, considering many different possible weights may gain us more power because we may capture the true relationship between the aggregated spatial summary statistics and sample-level outcome through randomly simulating weights.

spagg contains implementations for two different

approaches:

: in this approach,

spaggrandomly generates weights from a standard normal distribution which are used to construct a weighted mean of the Ripley’s K estimates obtained from each ROI. This process is repeated many times. For each random set of weights, the association between the weighted mean spatial summary and sample-level outcomes is tested. The resulting p-values are combined using the Cauchy combination test. This approach is contained in theensemble.avgfunction.: in this approach,

spaggrandomly generates weights from a standard normal distribution and uses these weights as well as the number of cells in each ROI to construct a weighted mean of Ripley’s K estimates. This process is repeated many times and the resulting p-values are combined using the Cauchy combination test. This approach is contained in thecombo.weight.avgfunction.

We now run these approaches to testing for the univariate analysis

using the cell.a.results data.frame we constructed above

which contains the Ripley’s K value at r=30.

# Run each ensemble test

ensemble.res <- ensemble.avg(data = cell.a.results,

group = "PID",

outcome = "out",

model = "logistic")

combo.res <- combo.weight.avg(data = cell.a.results,

group = "PID",

outcome = "out",

model = "logistic")

# Add the p-values to the results above

cell.a.pvals <- rbind.data.frame(

cell.a.pvals,

data.frame(

Method = c("Ensemble", "Combo"),

P.Value = c(ensemble.res$pval, combo.res$pval)

)

)

# Print the results

cell.a.pvals

#> Method P.Value

#> 1 Mean 0.006060067

#> 2 Diggle 0.023752779

#> 3 Baddeley 0.040878265

#> 4 Landau 0.205325277

#> 5 Ensemble 0.009344770

#> 6 Combo 0.020319545Here, the mean and the ensemble approaches yielded the lowest

p-values. The combo approach also yielded a low p-value. This suggests

some concordance among the methods in detecting a significant

association between the spatial distribution of cell type a

and case/control status.

We can also perform ensemble testing for the bivariate case. We show

how to do this below using the cell.ab.results object.

# Add the outcome back into the data

cell.ab.results <- left_join(cell.ab.results,

simdata %>% dplyr::select(id, PID, out) %>% distinct(),

by = c("id", "PID"))

# Run each ensemble test

ensemble.res <- ensemble.avg(data = cell.ab.results, group = "PID",

outcome = "out", model = "logistic")

combo.res <- combo.weight.avg(data = cell.ab.results, group = "PID",

outcome = "out", model = "logistic")

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

#> Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred

# Add the p-values to the results above

cell.ab.pvals <- rbind.data.frame(

cell.ab.pvals,

data.frame(

Method = c("Ensemble", "Combo"),

P.Value = c(ensemble.res$pval, combo.res$pval)

)

)

# Print the results

cell.ab.pvals

#> Method P.Value

#> 1 Mean 0.02393126

#> 2 Diggle 0.01362797

#> 3 Baddeley 0.05261129

#> 4 Landau 0.05261129

#> 5 Ensemble 0.02104012

#> 6 Combo 0.02473175Here, the ensemble and combo approaches yielded low p-values,

suggesting the spatial colocalization of cell types a and

b is associated with the outcome.